WE all know them.

The superstar sports men and women we love to call our own, even if they were not necessarily born in Australia.

Whether they migrated to Australia as youngsters, moved here seeking more opportunities or just decided to call the country home, we have opened up our arms and embraced them as part of the green and gold army.

They captured our imagination, even though they came from afar, and we cheered in revelled in their successes, as well as shared in their shattering defeats.

But they were always one of us.

From some of the greatest boxers of our time, to a pole vaulting champion and one out of left field, here are five of the best who took to the sporting arena after coming from afar and became legends Down Under.

Kostya Tszyu

You would have to have been living under a rock not to know who this bloke is.

You would have to have been living under a rock not to know who this bloke is.

One of the best boxers ever to compete under the Australian Flag, Tszyu’s thick Russian accent and broken English are a dead give away that his origins lay outside the country.

Tszyu was perhaps the most popular boxer among a see of wonderful personalities, having won the light welterweight belt four times.

Tszyu’s signature rat tail was among the most recognisable features on the sportsman, his toned body looked like a skinny, but rigid frame that belied the spectacular punching power he possessed. Many boxers who have stepped in the ring with him in the division say he is the hardest and most accurate puncher they have ever come up against.

Tszyu has a diverse background, born in a tiny Russian village to Korean-Mongol father and Russian mother. He competed at the 1988 Seoul Olympics for Russia and managed to avoid military service thanks to his boxing skills.

In 1991 his sport brought him to Australia. The Soviet Union had collapsed and Tszyu decided Australia would be his new home. Tszyu only lost twice in his storied 34 fight professional career, with one no contest.

A lover of animals, he once appeared on Harry’s Practice with his pet rottweiler Viking.

He retired in 2005 and, despite rumours almost every year, has never set foot back in the ring.

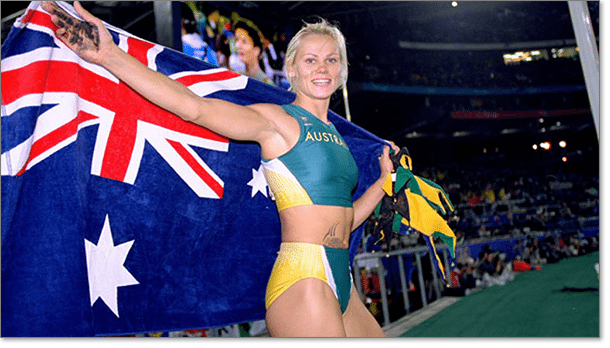

Tatiana Grigorieva

Has any athlete born outside Australia captivated the nation like the Russian born Olympian?

Grigorieva put the sport of pole vaulting on the map – and made it sexy. She became the pin up of the 2000 Sydney Olympics, among a sea of great Australian stories.

Once a national hurdler in mother Russia, Tatiana migrated to Australia in 1997 and three years later she almost stole the show from Cathy Freeman by winning a silver medal at the 2000 Olympics the same day the beloved runner took home gold.

From Russia to Australia, she became a household name over a 10-year career that also included a gold medal and world record at the 2002 Commonwealth Games, but she never quite reached the lofty heights of those stunning performances again.

She cashed in on her new fame and stunningly-athletic looks, posing in men’s magazines and making appearances on television shows like Gladiators and Dancing With the Stars.

Grigorieva was part of the Aussie track and field renaissance and will forever be etched in Aussie Olympic history. Even the great sports caller, Bruce McAvaney has her performance among his all time favourites, “that one night at the Oympics that changed everything for Australian sport.”

The mother of two can now be found endorsing such movements as Ocsober, encouraging Australians to take a step back from alcohol.

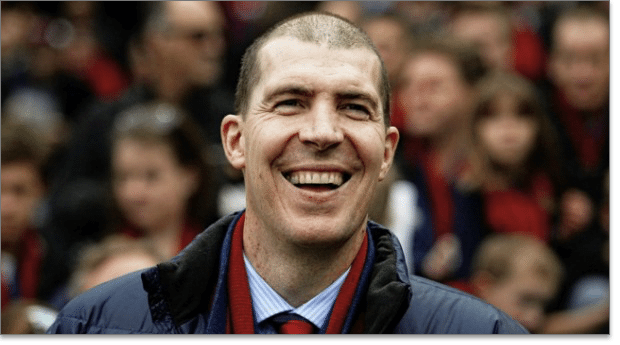

Jim Stynes

You would be hard-pressed to find a more beloved man in Aussie sport.

The Irish man was a pioneer of the then VFL’s international experience, becoming the first real success story of a player from overseas making good on footy’s biggest stage.

A gaelic football star, Stynes made the tough journey from Dublin to Melbourne to try his luck at Aussie Rules at the tender age of 18. He did it with aplomb, winning the 1991 Brownlow Medal and going on to play more consecutive games than any other AFL player, highlighting his ability to fight through pain and continue to produce. That was 244 games in a row – more than 10 seasons of one of the toughest sports in the world.

Already a legend on the field, few sports people – born here or abroad – could claim to match his contribution to Australian society. Stynes, a pioneer of the REACH Foundation, was a dual Victorian of the Year for his tireless work with youth. Stynes, an OAM, founded the not for profit organisation, which provides programs in schools to help promote mental health and wellbeing among children. REACH Foundation’s ethos – “That every young person has the support and self-belief they need to fulfil their potential and dare to dream.” – epitomised the attitude Stynes looked at life with, even as he faded through several surgeries to combat the terrible cancer that wracked his brain.

He fought his battle very publicly, rarely shying away from the spotlight, his efforts highlighting the need for more cancer research and no doubt generating plenty of donations along the way. Stynes was taken far too soon, losing his long battle with cancer in 2012 at the age of just 45. Thousands of Victorians turned out for a state funeral for the former Melbourne Demons president, a man who touched so many lives.

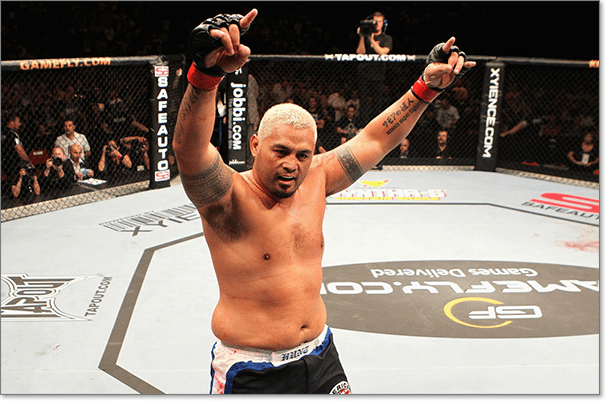

Mark Hunt

New Zealand born to Samoan parents, but Sydney based, The massive Kiwi has become perhaps the best known fighter in international circles, thanks to the wildly popular Ultimate Fighting Championship.

Hunt has become a cult figure in the UFC and, outside of the likes of Conor McGregor and Ronda Rousey, he is one of the biggest draw cards in the promotion.

The Super Samoan grew up in troubled times, but they actually helped him become a professional fighter. The story goes he had never given it a thought until a bouncer spotted him knocking several men out in a pub brawl and put him to work at his gym. The rest is history.

He has the policy of “anyone, anywhere, anytime” and that has often worked to his detriment, some times taking on three and four fights in a year, when others fight once or twice. He can’t say no and he loves is.

Was involved in what is widely regarded as the greatest UFC fight in history, when he and Antonio “Bigfoot” Silva fought out a majority draw decision in the first fight night ever hosted by Brisbane.

Silva failed a post-fight testosterone test, but that’s another story. Hunt’s star was set in concrete.

Hunt is very active on social media and comes across as a bloke next door who you could go over and have a beer and a yarn with – albeit a good bloke who could belt the living suitcase out of you if you upset him. Hunt is a father of six and has a great emphasis on family and helping the next generation of children avoid the mean streets he grew up on. He might fight for a living, but he is also setting an example for others to follow.

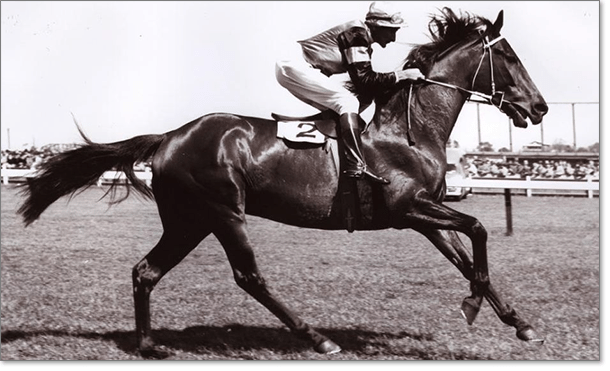

Phar Lap

Not technically a sports man or woman, but, out of all the adopted Aussies we could mention, Phar Lap stands alone for its legendary legacy.

Born in New Zealand, our most storied horse made his name in Australia, with all but one of his superb victories coming Down Under.

Phar Lap was born on October 4, 1926 and died on April 5, 1932. He became a beacon of hope in one of the bleakest times in Australia’s history, the Great Depression a litany of nicknames like Red Terror, Bobby, Big Red and Wonder Horse only adding to his intrigue.

Phar Lap was foaled in New Zealand, but trained in Australia by master trainer Harry Telford. Phar Lap had 51 starts for 37 wins, a remarkable record for the time, and counts the Melbourne Cup and two Cox Plates among its many wins.

A trip to Mexico signed his death knell, with his death in 1932 steeped in mystery and intrigue. Was it a sudden illness that struck him down? Did he meet with foul play? There is so much speculation, but there would only be a few who know the truth, and most of them would be pushing up daisies nowadays.

You can still see and honour Phar Lap today, his hide is on display at the Melbourne Museum, with his heart at the National Museum of Australia in Canberra. That heart was nearly double the size of a normal horse’s heart, weighing in at 6.2 kilograms, compared to the average of 3.2 kilograms. Conspiracy theorists say the heart is a fake, but his storied career has been immortalised in film several times.

You’ll see a bronze statue outside Flemington Race Course in Melbourne.